Award-Ceremony 2024

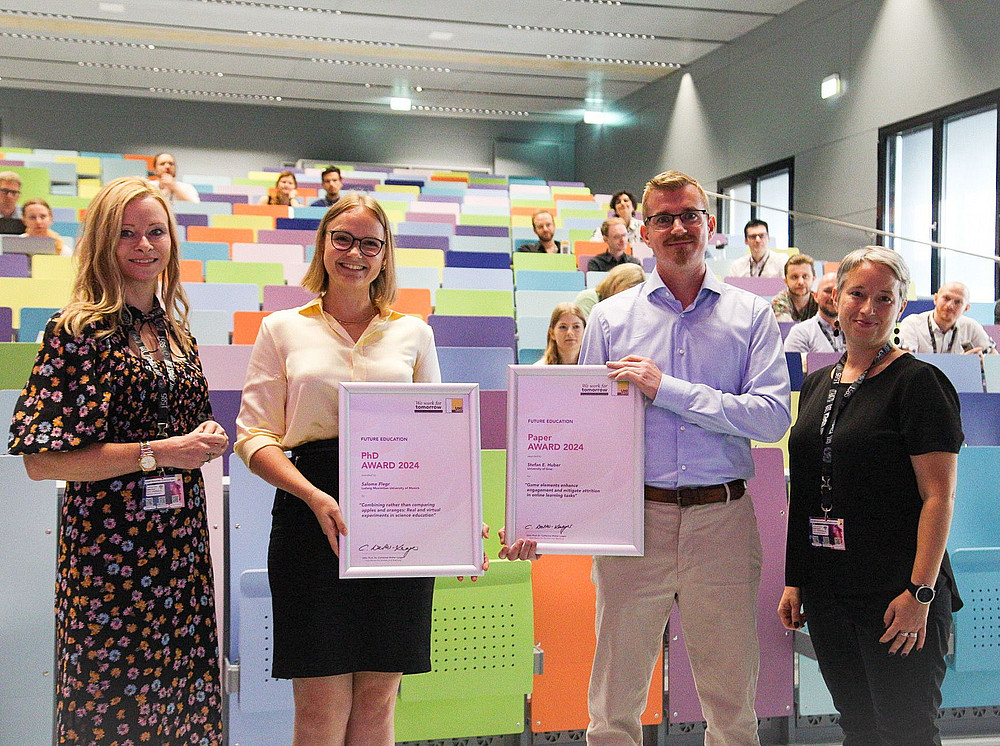

Der erste FUTURE EDUCATION Award wurde am 4. 9. 2024 im Rahmen der FUTURE EDUCATION Conference 2024 vergeben. Die Auszeichnung erging an Salome Flegr (TU Dresden) und an Stefan E. Huber (Universität Graz) für ihre hervorragenden Forschungsleistungen. Wir gratulieren herzlich!

Salome Flegr erhielt den PhD Award 2024 für ihre Dissertation mit dem Titel "Combining rather than comparing apples and oranges: Real and virtual experiments in science education".

Stefan Huber erhielt den Paper Award 2024 für seine Forschungsarbeit "Game elements enhance engagement and mitigate attrition in online learning tasks".

Dieser Preis soll herausragende transdisziplinäre Forschungsleistungen in den Forschungsgebieten, die auch die Konferenz abdeckt, anerkennen und auszeichnen. Der Award ist mit einem Preisgeld von je 1.000€ dotiert.

Biographie Salome Flegr

Salome Flegr wurde in Tübingen geboren. Nach ihrem Bachelor of Science in Physik, den sie 2015 an der Universität Ulm erlangte, verbrachte sie ein Erasmus Auslandssemester an der University of Surrey in Großbritannien. Ihren Master of Education: Gymnasiales Lehramt Physik und Mathematik erlangte sie 2019 an der Universität Stuttgart. Daraufhin war sie am Leibniz-Institut für Wissensmedien Tübingen (IWM) als wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin und Doktorandin tätig. Im Jänner 2023 promovierte sie schließlich an der TU Kaiserslautern (TUK) / RPTU in Kaiserslautern in Physikdidaktik. Ihre Dissertation mit dem Titel „Combining rather than comparing apples and oranges: Real and virtual experiments in science education“ erlangte sie mit Auszeichnung („summa cum laude“).

Ab 2022 war Salome Flegr als wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin und Postdoktorandin am Lehrstuhl für Didaktik der Physik an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München tätig, bevor sie im Herbst 2024 als Juniorprofessorin (W1) für Didaktik der Physik (mit Tenure Track auf W2) an die Technische Universität Dresden berufen wurde.

Mehrfach ausgezeichnet

Schon mehrfach wurde Salome Flegr für ihre fachlichen Kenntnisse und ihre Forschungsarbeit ausgezeichnet. 2012 erhielt sie von der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft den Schulpreis zum Abitur am Theodor-Heuss-Gymnasium Aalen für herausragende Leistungen im Fach Physik. Ihren Bachelorabschluss machte sie mit der ECTS-Note A, womit sie sich zu den besten zehn Prozent der vergangenen vier Semester des Studiengangs zählen darf. An der Universität Ulm hatte sie ein Deutschlandstipendium inne, von der Deutschen Telekom Stiftung erhielt sie ein FundaMINT-Stipendium. 2019 wurde sie als assoziierte Doktorandin in die Exzellenz-Graduiertenschule und in das Forschungsnetzwerk LEAD an der Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen aufgenommen. Beim LEAD Retreat Fall 2020 erhielt sie den Best Poster Award. Von 2020 bis 2022 war sie Junior-Fellow im Kolleg Didaktik:digital der Joachim Herz Stiftung.

Wir gratulieren recht herzlich zum FUTURE EDUCATION PhD Award der Universität Graz, mit dem Salome Flegr anlässlich der 1. FUTURE EDUCATION Conference 2024 für ihre Dissertation ausgezeichnet wurde!

Salome Flegr auf researchgate.net

Biographie Stefan E. Huber

Stefan E. Huber promovierte 2014 am Institut für Ionenphysik und Angewandte Physik an der Universität Innsbruck in Physik. 2010 hatte er dort bereits sein Magisterstudium in Physik abgeschlossen. 2018 folgten zuerst ein Bachelor und 2020 schließlich ein Master of science in Psychologie – ebenfalls an der Universität Innsbruck.

Von 2010 bis 2014 war er im Rahmen des Doktoratskollegs zu Computational Interdisciplinary Modelling (FWF DK+ Projekt Computational Interdisciplinary Modelling (DK-CIM) W1227-N16) Projektmitarbeiter (Doktorand) in der Forschungsgruppe Computational Chemistry am Institut für Ionenphysik und Angewandte Physik an der Universität Innsbruck.

2014 nahm er eine Stelle als Postdoc am Department für Chemie an der Technische Universität München an, bevor er Anfang 2015 als Postdoc ans Institut für Ionenphysik und Angewandte Physik an die Universität Innsbruck und zur Forschungsgruppe Computational Chemistry zurückwechselte, wo er teilweise parallel auch als Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Institut für Grundlagenwissenschaften der Ingenieurwissenschaften in der Abteilung für Festigkeitslehre und Strukturanalyse arbeitete.

2017 hatte er eine Postdoc-Stelle am Institut für Ionenphysik und Angewandte Physik an der Universität Innsbruck in der Forschungsgruppe Computational Molecular Physics inne, 2020 wurde er Oberassistent am Institut für Grundlagen der Ingenieurwissenschaften an der Universität Innsbruck in der Abteilung für Festigkeitslehre und Baustatik.

Im März 2022 wurde er Lehrbeauftragter am Institut für Psychologie an der Universität Innsbruck und seit Jänner 2023 ist er als Universitätsassistent am Institut für Psychologie an der Universität Graz in der Arbeitsstelle für Digitale Technologien und Psychologie tätig.

Seine Forschungsschwerpunkte liegen vor allem in den folgenden Bereichen:

- Kognitionspsychologie und Psychophysiologie: Analyse des menschlichen Blinzel- und Blickverhaltens; zeitliche, strukturelle (und fraktale) Aspekte der motorischen Aktivität, Wahrnehmung und Aufmerksamkeit; psychophysiologische Bewertung (Eye-Tracking, EKG, EDA, Analyse des Gesichtsausdrucks)

- Psychologie des Gedächtnisses, des Lernens und der Bildung: Lernanalytik; Psychophysiologie des Lernens; spielbasiertes Lernen und Lernspiele

- Computergestützte Methoden und Modellierung in Psychologie und Psychophysiologie: (nichtlineare) Zeitreihenanalyse; statistisches Lernen

Wir gratulieren herzlich zum FUTURE EDUCATION Paper Award, den Stefan E. Huber anlässlich der 1. FUTURE EDUCATION Conference 2024 für seine Publikation ausgezeichnet wurde!

Die Dankesrede von Stefan E. Huber anlässlich der FUTURE EDUCATION Award Ceremony 2024:

"I feel honored to be here today, and to be allowed to address you – on this occasion – with a couple of words. I appreciate your kind introduction to our work and I specifically thank you for honoring particularly this paper with this award. A work which, like most if not all scientific works, could only be achieved by joint effort and collaboration. And in this case, I am convinced that it would not exist at all without the indispensable groundwork of my colleagues and coauthors Dr. Rodolpho Cortez, Prof. Kristian Kiili, Antero Lindstedt, and Prof. Manuel Ninaus. So, it seems only fair to me to use some of this time given to me here to acknowledge their contribution, at least with a few words.

So, what was this contribution that made this work possible? Those who know me, also know, that before psychology I studied physics and that already back then, I was fascinated by the work of some of the early psychophysicists like Fechner or Weber, discovering fundamental law-like relations in human behavior; and by the fact of discovering them, exemplifying that something invariant enough to call it a natural law may even exist among all the noise and biases of human behavior and action.

And from my perspective, it was nothing less than such a fundamental relation, which my colleagues were after, long before I joined the group. Their specific question was: Is there a genuine effect of game- or playfulness on learning? With many years of experience in game-based learning, they have been well aware that games or elements of them can influence learning in many ways. Yet at the same time, learning is influenced by many other factors, like prior knowledge, or experience with a task or subject, personal dispositions, interests, motives, and many more. And such confounding factors, as we call them, make it very difficult to extract exactly that effect which a bit of added playfulness may exert on learning. However, the learning task and experimental design, which my colleagues had devised, would allow us, maybe not to minimize, but strongly reduce these confounding factors and provide some evidence for such a genuine effect.

In retrospective, the approach seems simple, obvious almost. Devise a learning task in which prior knowledge cannot play a role, which is basic enough not to be specific in relation to any subject domain, and with which learners can engage and disengage neither driven by necessity nor overly reward. And present two versions of this task, once in its original form and once with some game elements added to it. And then see what happens.

So, what is it that happens? What does a bit of playfulness do to learning? Let me put it like this. For me, a book is a good book if it makes me want to read more, and other books beyond it. And similarly, I would say, that a learning activity is a good one if it fuels my wish to learn more, and many other things beyond it. And I would claim that this is exactly what a little space for playfulness can, under some circumstances, do for learning. In the case of our study, it did not make people learn faster or more efficiently on average. But it helped them stick around a little longer, exploring and seeing through what otherwise they would have abandoned.

Admittedly, one could say, that this does not sound like much either. What use does it have educationally that people stick around, play around, maybe just fool around a little longer? Well, for some of them it means that they would learn something which otherwise they would not have. And in general, I would not underestimate the difference a little space for playfulness can make, even if this may only be noticed on rare occasions.

I lack the time to make this last point more explicit. I can only point towards a source that can. A piece[1] more than 80 years of age, composed by an educator named Abraham Flexner, titled “The usefulness of useless knowledge”. In this piece, Flexner describes many scientific discoveries not motivated by considerations of utility but by what Einstein[2] called “divine curiosity, play instinct” and “constructive fantasy”. My favorite among them, the discovery of electricity and all its consequences hopefully helps us grasp the global scale on which a little space for playful exploration may make a difference.

The future of education will reveal how much and what kind of space for such curiosity and playfulness we can provide in our research and teaching. Yet, I am convinced that this relation goes in both directions, that how much space we can grant those qualities in our education will to a considerable part also determine its future. Thank you."

[1] Flexner, A. (1939). The usefulness of useless knowledge. Harper’s Magazine, 179, 544-552.

[2] Einstein, A. (1930). In: Küpper, H. (2023). Sound document of Albert Einstein. Albert Einstein in the world wide web. einstein-website.de/en/sound-document/