Learning mathematics through play

Is it a smart idea to enrich learning material with game elements? Or are they more of a distraction? A project at the University of Graz deals with this central question of basic research.

Learning games have a good reputation. Playful elements motivate learners and trigger positive feelings. But is this reputation justified? After all, game elements can also be distracting and thus worsen learning outcomes and performance.

An international research team at the University of Graz addressed this fundamental question of whether game elements promote or even hinder learning. "Playful elements can distract from learning or learning material. We wanted to find out whether this distraction is balanced by learners' willingness to invest more resources in learning," says Manuel Ninaus of the University of Graz, who led the study. And he adds, "Learning games are a complex medium. It's not so easy to point exactly where the effect is, because there are quite different influencing factors."

Participants estimated the size of mathematical fractions

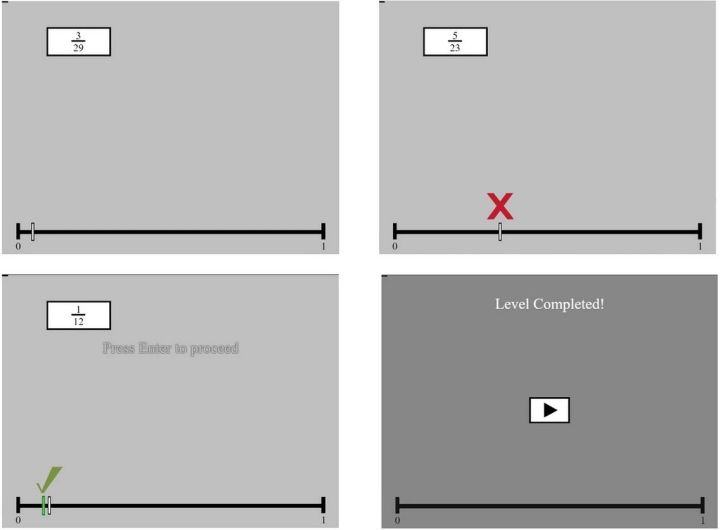

The question was examined using a training study on mathematical fractions with adults. The participants completed a 15- to 20-minute training session on each of five consecutive days, during which they had to master a number estimation task. Specifically, they were asked to estimate how large a mathematical fraction is and then indicate that value on a number line. "Number estimation tasks are well validated. They provide a good indication of how well number sizes are understood," Ninaus explains.

In this study, a group had to solve the tasks in the context of a computer game. They assumed the role of the virtual game character, "Semideus", and had to recover stolen money and a treasure from Zeus. They received rewards for correct answers. The game was thus enriched with graphic game elements and a story. In contrast, the second group had to solve the same tasks in a very neutrally designed computer program that worked according to the same game mechanics, but where the screen was gray and where they controlled a simple arrow symbol instead of "Semideus".

In game version, participants were more accurate

The result of the study was surprising in that the learning success from the pretest to the posttest was comparable between the groups. What was found, however, was that in the game version the participants were more accurate in their task, but somewhat slower, since the task presumably meant more to them and they were more willing to expend more (cognitive) resources. Thus, performance in training was better.

"Basically, people already learn better through games than without game elements. The learning success is greater," Ninaus says. "However, it is largely due to how the game is designed. The more closely the learning and game mechanics are intertwined, the less the game elements should distract but rather promote learning." And he emphasizes, "But: not all learning should be game-based. Some things don't work game-based, you just have to bite through it."